Bricked In

A photo essay

Published in Fresh Meat Journal 14

2024

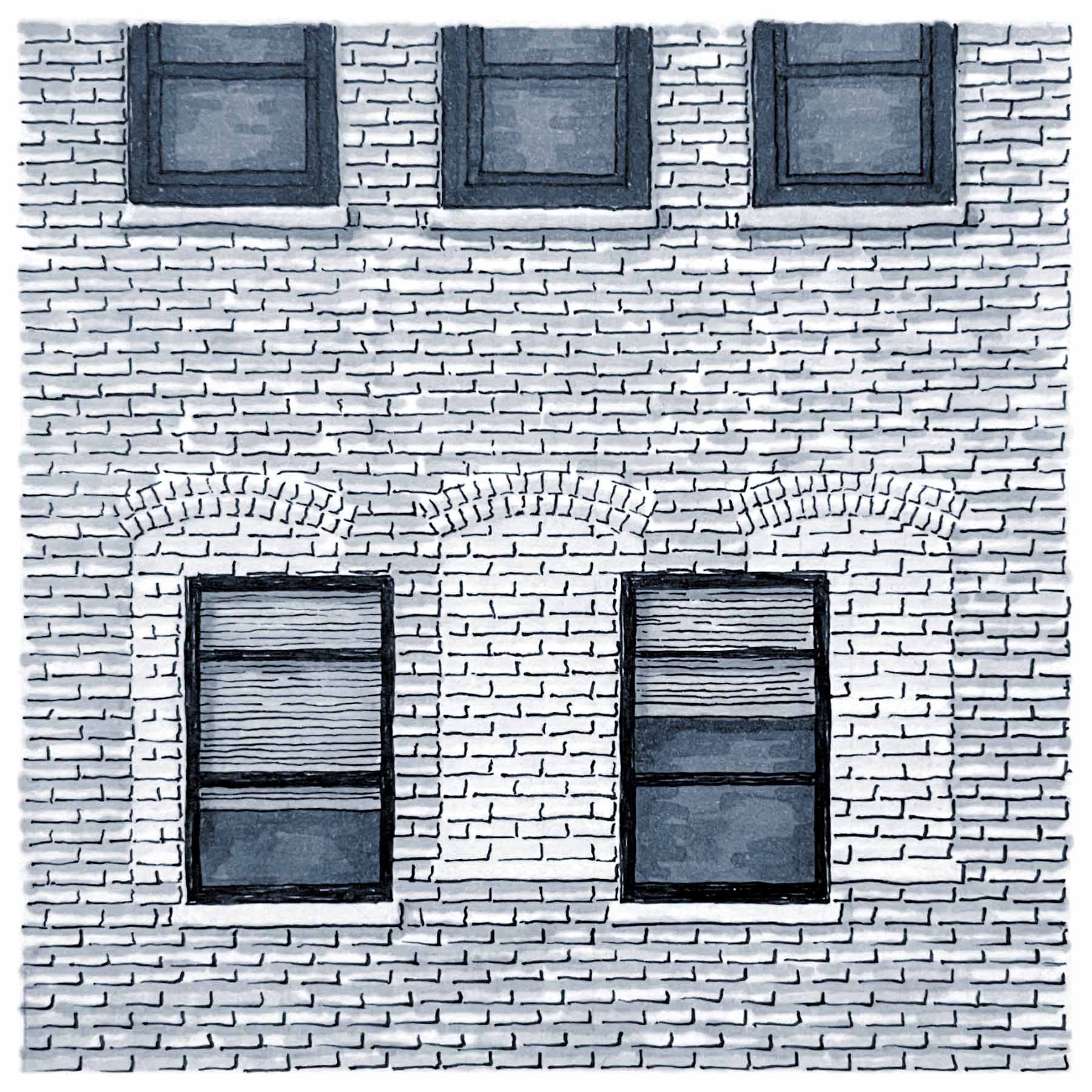

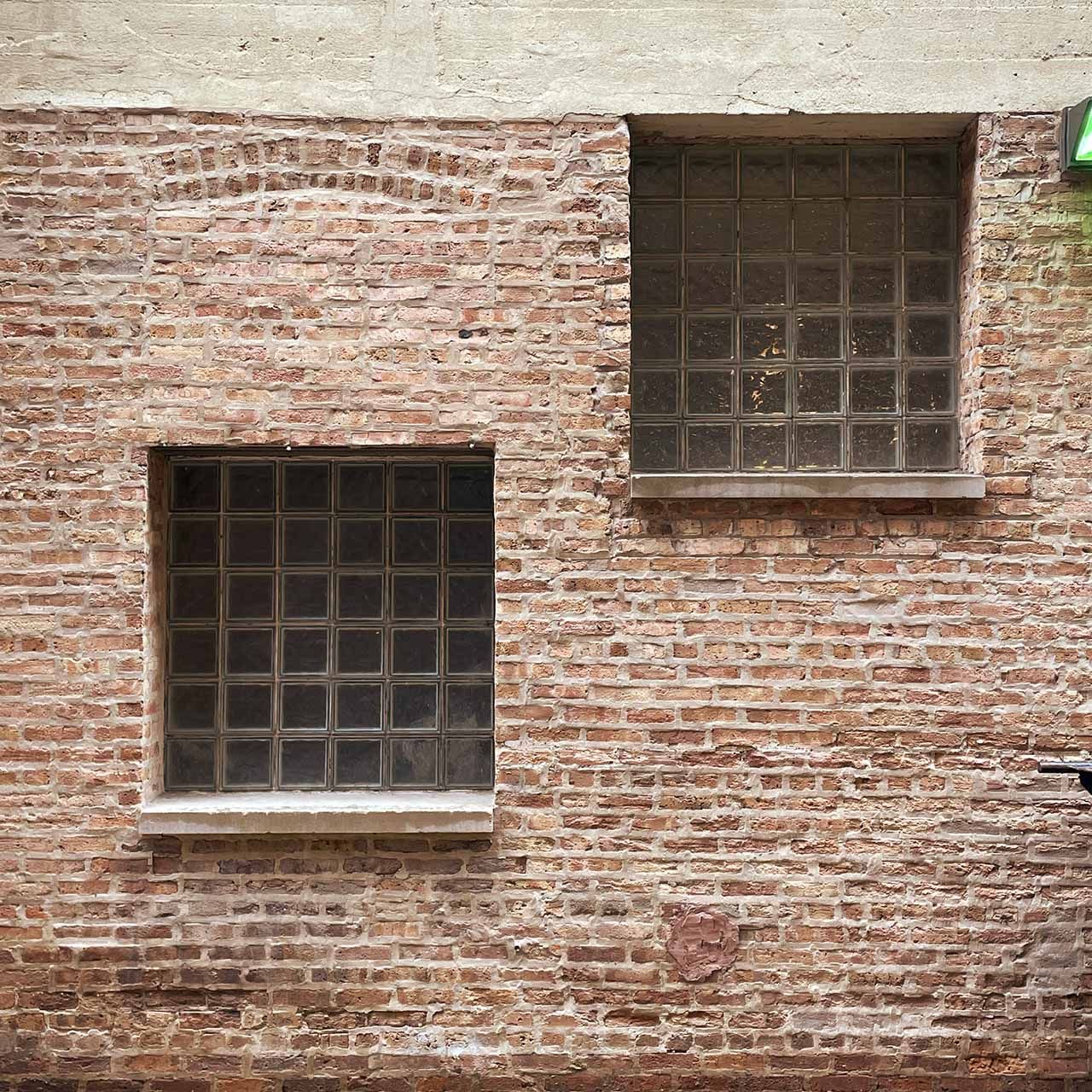

A patchy wall of Chicago common brick looms over the alley, speckled with shades of burnt umber and blackened terra cotta. On the second and third floors, the monolithic surface gives way to regularly spaced punched openings. Rectangular windows are set in rectangular black frames, aligned to the rectangular brick grid. Above each window, a shallow brick arch is the only break from orthogonality, the curve of the lintel engineered to distribute the weight of the bricks above the window to its sides.

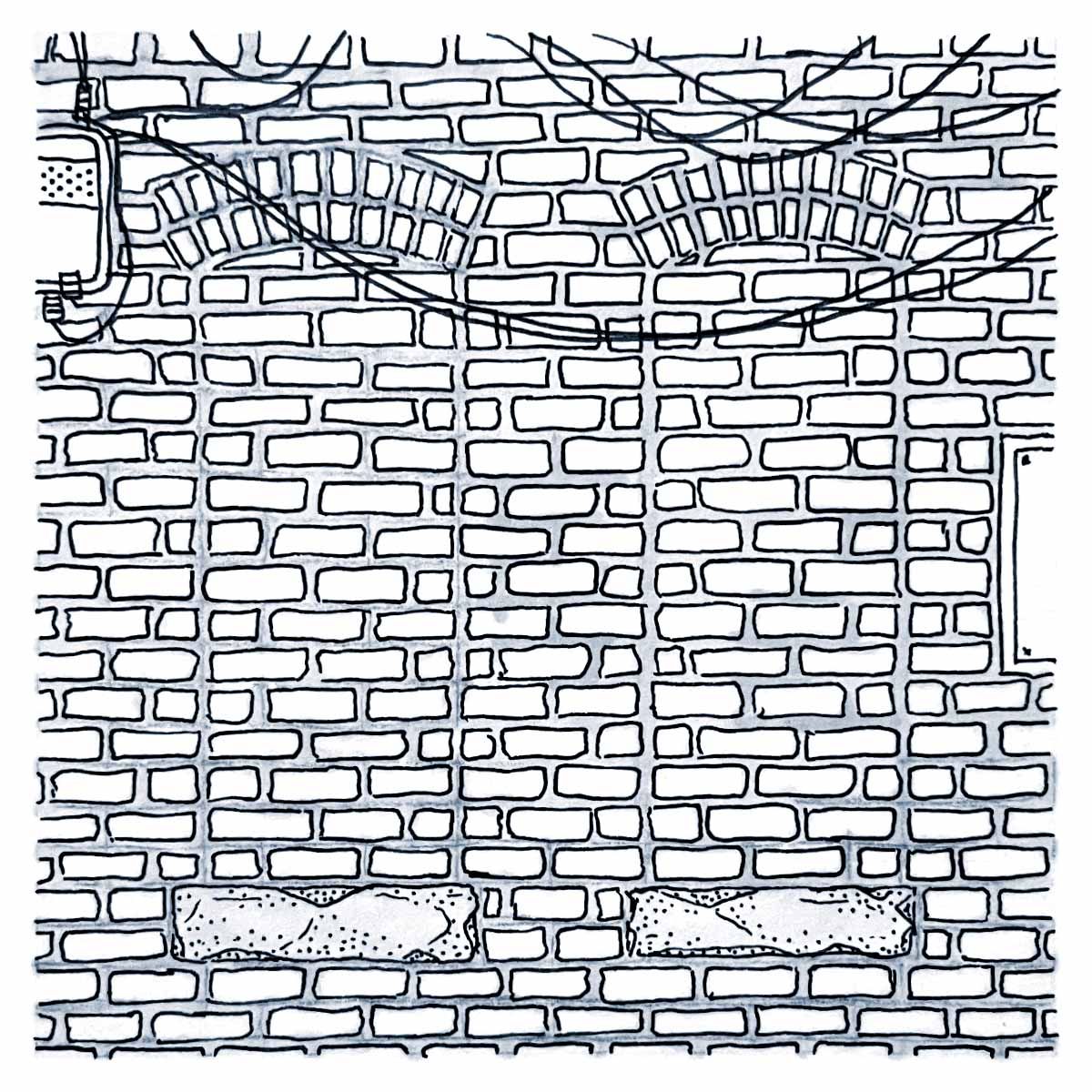

On the ground floor, the regularly spaced punched openings have been un-punched. What was an opening has now been filled with new brick, different in hue and shade from its surroundings, having been cooked from another clay at another time. Even if a perfect color match had been found for the infill, the repair job would be betrayed by the arch that remains, now stripped of its role in redirecting structural forces and imbedded in a continuous flat surface. The slight deflection in the mortar lines gives anyone looking close enough a clue that a window once lived here.

At the end of the row of non-windows, a curiosity appears. A window has been re-punched, not quite aligned with the one that came before. The sill is two courses lower and two bricks to the left. A steel lintel eliminates the need for a reinforcing arch, aligning the window on all edges to the rectangular grid. This section of the building has an identity crisis, undecided on whether it wants to be a window or a wall.

It's easy to argue that this window is an affront to architecture. The original vision of the facade has been deformed, patched by a tradesperson with mismatched bricks. The undesigned change of one architectural element has disturbed the architectural whole. It is a scar from a dodgy surgery and it is ugly.

But it was never intended to be a cosmetic surgery. The needs of the occupants had changed, and the architecture no longer met those needs. A window cut into a bricked in window is not a sign of indecision, but is a chronology of multiple separate decisions over a larger timespan. The interior needed a wall where there was a window, and then later needed a window where there was a wall. The ugliness comes not from those decisions, but from the inflexibility of the material to adapt to changes. It is the brick that betrays itself.

The weathering of brick, stone, wood, and other natural materials express age, allowing humans to participate in processes beyond their lifespan. The lichen on Stonehenge, the rough edges of missing stone of the Colosseum, and the greying wood of the doors of Notre Dame are all material properties that connect visitors across time. The bricked in window unintentionally distills this phenomena into a single architectural detail. Old and new are merged into a solidified material form, writing their history into a wall.

Two points in time, bonded with a little bit of mortar.

Next project:

A Longer Now